Hadith Qudsi

Sacred tradition or al-ḥadīth al-qudsī (Arabic:الحدیث القدسی) is non-Quranic sayings of God, which is quoted by the Prophet (s). It is also called al-ḥadīth al-rabbānī (Arabic:الحدیث الرّبّانی) or al-hadīth al-ilāhī (divine tradition).

In these hadiths, the content is from God and the words are from the Prophet (s). The Prophet (s) receives the content either through an angel or by direct inspiration. These hadiths usually begin with the phrases "Qal Allah" (God said) or "Yaqul Allah" (God says).

Among the differences between sacred traditions and the Qur'an is the fact that, unlike the former, the latter is a miracle even verbally. There are also thematic differences between the Qur'an and sacred traditions. Non-scriptural sayings of God which are quoted by other prophets (a) are also categorized as sacred tradition. The themes found in sacred traditions are mostly ethical and mystical.

The most important disagreement about sacred traditions is whether their words are also revealed or not. Most of these traditions are transmitted by Anas b. Malik, Abu Hurayra, Ibn 'Abbas, and Imam Ali (a).

Terminology

The word "qudsi" in the term "hadith qudsi" (sacred tradition) means pure or sacred.[1] As to why this adjective is used, it seems more probable that it has been because the content of sacred traditions comes from God the Sacred (al-Quddus).[2] Al-Kirmani[3] is among the earliest writers who used the three adjectives "qudsi", "ilahi", and "rabbani" for these hadiths. Among the three adjectives, ilahi seems to have been used earlier and more widely. Ibn Kathir also used the term ilahi to refer to sacred traditions.[4] However, when the term hadith qudsi was later used, it became quickly popular and the term "hadith ilahi" was replaced with it. According to Graham,[5] Abd Allah b. al-Hasan al-Tayyibi (d. 743/1342-3) was the first person to use the term hadith qudsi, but it seems that Amir Hamid al-Din (d. 667/1268-9) used it before him.[6]

Other figures who used the term hadith qudsi in their works include:

- Al-Qaysari (d. 751/1350-1) in his commentary on Fusus al-hikam[7]

- Al-Shahid al-Awwal (d. 786/1384) in his al-Qawa'id wa-l-fawa'id[8]

- Al-Kirmani in his commentary on Sahih al-Bukhari[9]

- Al-Jurjani (d. 816/1413-4) in al-Ta'rifat[10]

- Ibn Hajar al-'Asqalani (d. 852/1448-9) in Fath al-bari[11]

Other terms have also been used for sacred tradition, including al-ahadith al-mala'ikiyya (angelic traditions) and ahadith al-mala'ikat al-kiram wa-l-jann (the hadiths of the noble angels and jinn). Prior to the widespread usage of these terms, scholars have quoted these hadiths, albeit without using a particular title for them.

Definition

Scholars of hadith have mentioned certain characteristics for sacred traditions and their differences with the Qur'an. In all the definitions of sacred tradition, the common feature is it is a non-Qur'anic saying of God which is quoted by the Prophet (s). Scholars have mentioned various numbers for the defining features for sacred tradition.

Al-Shaykh al-Bahai, for example, has mentioned only one feature, whereas al-Bulushi has mentioned fourteen features. The most important aspects of sacred traditions that have been discussed are the following:

- Their letters

- Their contents

- The way in which they were inspired to the Prophet (s)

- Their miraculous nature

- The permissibility of touching them without having ritual purity

- The permissibility of reciting them in prayers

In Hadith Sciences

Although one can find discussions on sacred traditions in the works of al-Jurjani, Abu l-Baqa', and al-Tahanawi, the first discussion of the topic in the Sunni sources of hadith sciences seems to have started with al-Qasimi's (d. 1332/1913-4) Qawa'id al-tahdith. Despite the late compilation of the Shiite works in the field of "Dirayat al-hadith" from hadith sciences, the term hadith qudsi appears in the early works in this field, such as Shaykh Bahai's al-Wajiza and Mashriq al-shamsayn and Mir Damad's al-Rawashih al-samawiyya, and then in the subsequent works.

Themes

Among the themes found in sacred traditions are mystical and ethical themes, such as self-purification, sincerity, repentance, remembering God, merits of righteous deeds, the importance of socializing with pious people, dealing with people kindly, enjoining good and forbidding evil, God's generosity in rewarding people, and the stories of the past prophets (a). No obligations have been legislated in these hadiths; rather, they have only emphasized the reward or punishment of some deeds and rituals and the importance of recommended acts. In Shiite sources, those sacred traditions that address the issue of imamate have been categorized separately. Sacred traditions have influenced, for the most part, mystical and ethical works, and some of the Sufi doctrines were formed essentially under their influence or were later linked to them. Most usages of these traditions can be seen in the works of Ibn Arabi. However, the impact of sacred traditions is not limited to mystical or ethical works; rather, they have influenced some jurisprudential works and even some works on the principles of jurisprudence (usul al-fiqh). Some of these hadiths contain conversations between God and the people of Paradise or Hell on the Day of Judgment, and some of them relate to God's sayings which the Prophet (s) received on the Night of Ascension.

Verbal Inspiration

The most important discussion with regard to sacred traditions is on whether or not they are verbally inspired. Some scholars believe that, like other hadiths, their wording is from the Prophet (s). Based on this viewpoint, the difference between these hadiths and the Qur'an is clear, but the difference between them and the other hadiths would only be the fact that the attribution of sacred traditions to God is more emphatic. Some other scholars maintain that sacred traditions, like the Qur'an, are also divinely inspired. This viewpoint is attributed to some early Muslim scholars as well but needs further evidence. Based on this viewpoint, sacred traditions become clearly distinct from other hadiths, but the difference between them and the Qur'an becomes somehow vague.

Reception

There is also disagreement among scholars as to how the Prophet (s) received these hadiths. According to one viewpoint, he received the Qur'an through Jabra'il (Gabriel), but Jabra'il was not the necessarily the agent of transmitting the content of sacred traditions to the Prophet (s). According to another viewpoint, Jabra'il could also have transmitted sacred traditions to the Propeht (s).

Sacred traditions are considered to have been inspired mostly in dreams, visions, and so forth. Sacred traditions are sometimes considered to be totally non-revelational, but sometimes they are considered hidden revelations in contrast to the Qur'an, which is regarded as the manifest revelation.

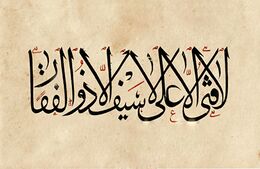

Formulas

According to al-Tahanawi, two formulas are used in transmitting sacred traditions: one used by the salaf (the first three generations of Muslims), which is "The Messenger of God said among what he narrates from his Lord"; and one used by the subsequent generations: "God Almighty said among what the Prophet (s) narrated from Him." The scholars after al-Tahanawi also mentioned only these two formulas. The purpose of using the two formulas was to distinguish them from Qur'anic materials. It should be noted, however, that one can find other formulas in the beginning of sacred traditions as well.

Sacred traditions can be divided into two types: those which quote a saying of God only and those which quote something like a story containing a saying of God.

Sunni hadith scholars accept only those sacred traditions that are narrated by Prophet Muhammad (s), but Sufis have reported certain sayings of God from the Bible via people like Wahb b. Munabbih and Ka'b al-Ahbar. For instance, Ibn Arabi has devoted a chapter of his Mishkat al-anwar to this kind of sacred traditions and mentioned the translation of forty chapters of the Torah, attributed to Imam Ali (a), from Hebrew to Arabic. Some of the sacred traditions attributed to the Prophet (s) start with the phrase "It is written in the Torah" or "It is written in the Gospel."

Authenticity

The authenticity of sacred traditions is also a matter of discussion among scholars. This discussion can be usually found in the introductions to the works on hadith sciences and sometimes in the discussion on the common between authentic and inauthentic. However, scholars agree that among sacred traditions, authentic (sahih), good (hasan), and weak (da'if) hadiths can be found. Some Sunni scholars have pointed out the inauthenticity of some famous sacred traditions, such as Hadith al-Kanz and Hadith Lawlak. In the hadith collections that categorize sacred traditions according to their authenticity, almost half of them are classified as weak. Sacred traditions have been criticized both for their contents and for their lack of the chains of transmission. Because of this, Massignon regarded them as a kind of Sufi "ecstatic sayings" (shathiyyat). However, the lack of the chain of transmission in these hadiths does not necessarily mean that they are inauthentic but that the Sufis did not care much about mentioning the chains of transmitters. The fact that many sacred traditions can be found in authentic Sunni and Shiite hadith sources and some of them are even adduced in jurisprudential works supports their authenticity.

Quantity

The number of sacred tradition is said to be one-hundred in some early sources, and in some others two-hundred. This number has increased in the later sources; for instance, in Mawsu'at al-ahadith al-qudsiyya al-sahiha wa-l-da'ifa, the number of sacred traditions, whether authentic or inauthentic, has amounted to 919. However, no thorough investigation has been conducted in this regard, and the differences are sometimes due to different criteria and even arbitrary judgments.

Transmitters

According to al-Jami' fi-l-ahadith al-qudsiyya by Abd al-Salam Allush, most sacred traditions are transmitted by Anas b. Malik, then Abu Hurayra, Ibn Abbas, and Imam Ali (a). In Shiite sources, sacred traditions are narrated through the Imams (a) from the Prophet (s), from the past prophets (a), from Jabra'il (Gabriel), or sometimes directly from God. Some sacred traditions contain a conversation between God and a prophet (a)—in most cases, Prophet Moses (a) or David (a).

Books

Sacred traditions can be found throughout Shiite and Sunni hadith sources in various sections. However, there are also distinct collections of sacred traditions. The earliest collection in this regard is al-Mawa'iz fi l-ahadith al-qudsiyya, which is attributed to al-Ghazali. If this attribution is not correct, the earliest work is al-Ahadith al-ilahiyya by Zahir b. Tahir b. Muhammad al-Nishaburi. Among the most well-known compilers of sacred traditions are Ibn Arabi, Mulla Ali Qari, Muhammad Abd al-Ra'uf al-Manawi, and Muhammad al-Madani. Among Shiite works on sacred traditions, the earliest work is said to have been al-Balagh al-mubin, attributed to Sayyid Khalaf al-Huwayzi (d. 1074/1664). After that, the earliest work is Al-Jawahir al-saniyya fi l-ahadith al-qudsiyya by Shaykh Hurr al-'Amili.

Notes

- ↑ Ibn Fāris, Muʿjam maqāyīs al-lugha; Ibn Manẓūr, Lisān al-ʿArab, under the word "Quds".

- ↑ Kirmānī, Sharḥ ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, vol. 9, p. 79; Balūshī, al-Aḥādīth al-qudsīya, p. 7; Ṭaḥan, Taysīr muṣṭalaḥ al-ḥādīth, p. 127.

- ↑ Kirmānī, Sharḥ ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, vol. 9, p. 79.

- ↑ Balūshī, al-Aḥādīth al-qudsīya, p. 54.

- ↑ Graham, Divine word and prophetic word, p. 57.

- ↑ Tahāuwī, Mawsūʿa kashshāf iṣṭilāḥāt al-funūn wa al-ʿulūm, vol. 1, p. 630.

- ↑ Qayṣarī, Sharḥ fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam, p. 372.

- ↑ Shahīd al-Awwal, al-Qawāʿid wa-l-fawāʾid, part 1, p. 75; part 2, 107-181.

- ↑ Kirmānī, Sharḥ ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, vol. 9, p. 79.

- ↑ Jurjānī, al-Taʿrīfāt, p. 113.

- ↑ Ibn Ḥajar, Fatḥ al-bārī, vol. 13, p. 409.

References

- Bukhārī, Muḥammad b. Ismāʿīl al-. Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. Edited by Muḥammad Dhihnī Afandī. Istanbul: 1401 AH.

- Ḥākim al-Nayshābūrī. Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-. Al-Mustadrak ʿala l-ṣaḥīḥayn. Edited by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Marʿashlī. Beirut: 1406 AH.

- Ḥusaynī Amīnī, Muḥsin. Al-Aḥādiīh al-qudsīyya al-mushtaraka bayn al-Sunna wa al-Shīʿa. Tehran: 1425 AH.

- Hurr al-ʿĀmilī, Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan. Al-Jawāhir al-sanīyya fī l-aḥādīth al-qudsīyya. Qom: Offset, [n.d].

- Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī, Aḥmad b. ʿAlī. Fatḥ al-bārī bi sharḥ ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. Bulaq: 1300-1301 AH.

- Jurjānī, ʿAlī b. Muḥammad. Kitāb al-taʿrīfāt. Edited by Ibrāhīm Ābyārī. Beirut: 1405 AH.

- Muḥyi al-Dīn al-ʿArabī, Muḥammad b. ʿAlī. Al-Futūḥāt al-makkiyya. Edited by ʿUthmān Ismāʿīl Yaḥyā. Cairo:

- Shawkānī, Muḥammad. Nayl al-awṭār min aḥādīth sayyid al-akhyār: sharḥ muntaqā al-akhbār. Beirut: 1973.

- Tirmidhī, Muḥammad ibn ʿĪsā al-. Al-Jāmiʿ al-ṣaḥīḥ. Edited by Abd al-Wahhab 'Abd al-Latif. Beirut: 1403 AH.

- Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī, Shahāb al-Dīn. Fatḥ al-bārī; sharḥ ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. Bulaq: 1300-1301. Beirut: Offset, [n.d].

- Ibn Fāris. Muʿjam maqāyīs al-lugha.

- Ibn Manẓūr, Muḥammad b. Mukarram. Lisān al-ʿArab.

- Qayṣarī, Dāwūd b. Maḥmūd al-. Sharḥ fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam.

- Kirmānī, Muhammad b. Yusuf. Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī bi sharḥ al-Kirmānī. Beirut: 1401 AH.

- Shahīd al-Awwal, Muḥammad b. Makkī. Al-Qawāʿid wa-l-fawāʾid: fī al-fiqh wa al-'usul wa al-'arabiyya. Edited by Abd al-Hadi Hakim. Najaf: 1399 AH. Qom: Offset, [n.d].

- Tahāuwī, Muhammad A'la b. Ali. Mawsūʿa kashshāf iṣṭilāḥāt al-funūn wa al-ʿulūm. Edited by Rafiq al-'Ajam and Ali Dahruj. Beirut: 1996.

- Māmaqānī, Muḥammad Ridā. Mustadrakāt miqbās al-hidāya fī ʿilm al-dirāya in ʿAbd Allāh Māmaqānī's Miqbās al-hidāya fī ʿilm al-dirāya. volume 5-6. Qom: 1413 AH.