Qur'an 2:129

| |

| Verse's Information | |

|---|---|

| Sura | al-Baqara |

| Verse | 129 |

| Juz' | 1 |

| Content Information | |

| Place of Revelation | Medina |

| About | Supplication of Prophet Ibrahim (a) and Prophet Isma'il (a) |

| Related Verses | Qur'an 2:127 • Qur'an 2:128 |

Qur'an 2:129 (Arabic:آية 2 من سورة البقره) refers to the supplication of Prophet Ibrahim (a) and Prophet Isma'il (a) while building the Ka'ba. They asked God to raise a prophet from their Muslim descendants to realize the goals of the divine mission among the people. In this prayer, three goals are outlined for raising the Messenger: reciting the Book, teaching Wisdom (Hikma), and purifying humans. Citing a Prophetic Hadith, Shi'a exegetes consider the word "Rasul" (Messenger) in the verse to specifically refer to Prophet Muhammad (s) and interpret the "Book" as the Qur'an.

According to their interpretation, wisdom refers to a set of deep teachings, the results and secrets of divine laws, and the knowledge of the realities of the universe. Alongside teaching the Book and Wisdom, purification (Tazkiya) is posited as a fundamental goal of the mission; a purification that includes cleansing humans from kufr (disbelief), shirk (polytheism), deviation, and removing moral vices and various sins.

In explaining this verse, Ayatollah Jawadi Amuli considers the ultimate goal of the mission of the prophets, especially the Prophet of Islam (s), to be the purification of the human soul and spirit; thus, teaching the Book and Wisdom is merely a means to achieve this transcendent goal.

Prayer for the Realization of Prophets' Goals

In Verse 129 of Qur'an 2, Prophet Ibrahim (a) and Isma'il (a) asked God to send a prophet from their own lineage to realize three goals of the prophetic mission: reciting divine signs to the people, teaching Wisdom, and purification.[1] Al-Shaykh al-Tusi considered the "Book" in this verse to be the Qur'an;[2] however, Ali Mishkini believes that the implication of teaching the Book in the verse includes teaching the Qur'an as well as past Heavenly Books.[3]

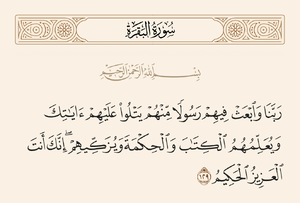

| “ | رَبَّنَا وَابْعَثْ فِيهِمْ رَسُولًا مِنْهُمْ يَتْلُو عَلَيْهِمْ آيَاتِكَ وَيُعَلِّمُهُمُ الْكِتَابَ وَالْحِكْمَةَ وَيُزَكِّيهِمْ ۚ إِنَّكَ أَنْتَ الْعَزِيزُ الْحَكِيمُ

|

” |

| — Qur'an 2:129 | ||

Connection with Previous Verses

According to verses 127 and 128 of Qur'an 2, when Ibrahim (a) and Isma'il (a) were engaged in rebuilding the Ka'ba, they prayed that God accept the construction of the Ka'ba from them, make them and their descendants submissive to God's command, teach them the rituals and how to worship God, and accept their Repentance.[4] Their final request in these prayers, which appears in Qur'an 2:129, was for the sending of a prophet from their own lineage for the divine guidance of the society.[5]

Who is the Prophet of Guidance?

Many Shi'a exegetes, citing a Prophetic Hadith, believe that the word "Rasul" (Messenger) in Qur'an 2:129 refers to Prophet Muhammad (s).[6] In this narration, the Prophet (s) considered himself the result of the prayer of his father, Ibrahim.[7] It is said that the prayer and the accompanying evidence indicate that the Messenger in this verse is Prophet Muhammad (s), because the city for which Ibrahim asked security and sustenance for its inhabitants was Mecca.[8] Additionally, only Muhammad (s) was sent as a prophet in that city from the lineage of Isma'il (a).[9] However, Abdullah Jawadi Amuli does not accept the restriction of the meaning of Rasul to Prophet Muhammad (s) alone and counts him as one of the instances of this prayer.[10]

Pointing to the word "minhum" (from among them) in this verse, Makarim Shirazi believes that prophets must be of the human race; because by possessing human attributes and instincts, they can better understand the pains, needs, and problems of the people, and since they reached the position of prophethood despite having those same instincts and attributes, they will be worthy role models for the people.[11]

Purification of Human as a Result of Teaching Book and Wisdom

According to Jawadi Amuli, in Qur'an 2:129, teaching is placed before purification (Tazkiya); because teaching and knowing the laws and teachings play a preparatory role for the cultivation and purification of the human being. However, the importance of purification is actually greater than teaching and is considered the ultimate goal of the prophets, as the main goal is the purification of the human soul and spirit, and teaching is merely a means to reach that high goal.[12] However, Sadeqi Tehrani, pointing to three other verses of the Qur'an where the word "tazkiya" appears before teaching, concludes that in the mission of the Prophet, the refinement and moral training of the people take precedence over teaching them.[13]

Exegetes have pointed to various meanings in explaining the term Wisdom (Hikma) in Qur'an 2:129. For example, in Tafsir-i nimuna, it is interpreted as a set of knowledge, secrets, and results of divine laws and regulations that the Prophet explains to the people.[14] Sayyida Nusrat Amin also considers it to mean knowing the reality of beings to the extent of human capacity. She also mentions the views of other exegetes, including knowledge of religion, the Sunna of the Prophet (s), knowledge of laws that are understood only through the guidance of the Messenger, and also a light that illuminates the human heart. In her view, all these meanings are manifestations of the same knowledge of the reality of things, which forms the basis of wisdom.[15] In Tafsir-i rawan by Ali Mishkini, wisdom is also defined as the set of independent dictates of reason, knowledge of the realities of beings, and the laws of Shari'a.[16]

The purpose of purification of people is considered to be cleansing them from kufr, shirk, deviation, moral vices, and various types of sins, the highest degree of which is infallibility.[17] Fakhr al-Razi, a Sunni exegete, believes that the "purification by the Prophet" means outward teaching and guidance, not influence on the inner self of humans, because the Prophet does not have such power, and if he did, using it would imply Determinism (jabr). Jawadi Amuli states that contrary to Fakhr al-Razi, by God's permission, the Prophet has the power of spiritual influence on human souls, without their free will being negated; and even if this influence were determinism, it would not contradict Fakhr al-Razi's own deterministic basis.[18]

Notes

- ↑ Makārim Shīrāzī, Tafsīr-i nimūna, 1374 Sh, vol. 1, pp. 456-457; Bānū Amīn, Makhzan al-ʿirfān, 1361 Sh, vol. 2, pp. 86-87.

- ↑ Ṭūsī, Al-Tibyān, vol. 1, p. 467.

- ↑ Mishkīnī, Tafsīr-i rawān, 1392 Sh, vol. 1, p. 143.

- ↑ Makārim Shīrāzī, Tafsīr-i nimūna, 1374 Sh, vol. 1, pp. 454-456.

- ↑ Makārim Shīrāzī, Tafsīr-i nimūna, 1374 Sh, vol. 1, pp. 454-456.

- ↑ See: Jawādī Āmulī, Tafsīr-i Tasnīm, 1388 Sh, vol. 7, p. 87; Ṭūsī, Al-Tibyān, vol. 1, p. 466; Rāzī, Rawḍ al-jinān, 1371 Sh, vol. 2, p. 173.

- ↑ Baḥrānī, Al-Burhān, 1373 Sh, vol. 1, p. 334; Ṣadūq, Man lā yaḥḍuruh al-faqīh, 1413 AH, vol. 4, p. 369.

- ↑ Qur'an 2:126.

- ↑ Karamī, Natāʾij al-fikr, 1426 AH, vol. 2, p. 58.

- ↑ Jawādī Āmulī, Tafsīr-i Tasnīm, 1388 Sh, vol. 7, p. 87.

- ↑ Makārim Shīrāzī, Tafsīr-i nimūna, 1374 Sh, vol. 1, p. 458.

- ↑ Jawādī Āmulī, Tafsīr-i Tasnīm, 1388 Sh, vol. 7, pp. 100-102.

- ↑ Ṣādiqī Tihrānī, Al-Furqān, 1406 AH, vol. 2, pp. 160-161.

- ↑ Makārim Shīrāzī, Tafsīr-i nimūna, 1374 Sh, vol. 1, pp. 456-457.

- ↑ Bānū Amīn, Makhzan al-ʿirfān, 1361 Sh, vol. 2, p. 85.

- ↑ Mishkīnī, Tafsīr-i rawān, 1392 Sh, vol. 1, p. 143.

- ↑ Ṭayyib, Aṭyab al-bayān, 1378 Sh, vol. 2, p. 199.

- ↑ Jawādī Āmulī, Tafsīr-i Tasnīm, 1388 Sh, vol. 7, pp. 86-87.

References

- Abū l-Futūḥ al-Rāzī, Ḥusayn b. ʿAlī. Rawḍ al-jinān wa rawḥ al-janān fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān. Mashhad, Āstān-i Quds-i Raḍawī, 1371 Sh.

- Baḥrānī, Hāshim b. Sulaymān al-. Al-Burhān fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān. Qom, Bunyād-i Biʿthat, 1373 Sh.

- Bānū Amīn, Nuṣrat Begum. Makhzan al-ʿirfān dar ʿulūm-i Qurʾān. Tehran, Nahḍat-i Zanān-i Musalmān, 1361 Sh.

- Jawādī Āmulī, ʿAbd Allāh. Tafsīr-i Tasnīm. Qom, Markaz-i Nashr-i Isrāʾ, 4th ed., 1388 Sh.

- Karamī, Muḥammad. Natāʾij al-fikr fī sharḥ al-Bāb al-ḥādī ʿashar. Qom, Mahdī Yār, 1426 AH.

- Makārim Shīrāzī, Nāṣir. Tafsīr-i nimūna. Tehran, Dār al-Kutub al-Islāmiyya, 1374 Sh.

- Mishkīnī, ʿAlī. Tafsīr-i rawān. Qom, Dār al-Ḥadīth, 1392 Sh.

- Ṣādiqī Tihrānī, Muḥammad. Al-Balāgh fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān bi-l-Qurʾān. Qom, Maktabat Muḥammad al-Ṣādiqī al-Tihrānī, 1419 AH.

- Ṣadūq, Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-. Man lā yaḥḍuruh al-faqīh. Qom, Daftar-i Intishārāt-i Islāmī, 2nd ed., 1413 AH.

- Ṭayyib, ʿAbd al-Ḥusayn. Aṭyab al-bayān fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān. Tehran, Intishārāt-i Islām, 1378 Sh.

- Ṭūsī, Muḥammad b. Ḥasan al-. Al-Tibyān fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān. Beirut, Dār Iḥyāʾ al-Turāth al-ʿArabī, n.d.