Qur'an 4:82

| |

| Verse's Information | |

|---|---|

| Sura | Sura al-Nisa (Qur'an 4) |

| Verse | 82 |

| Juz' | 5 |

| Content Information | |

| Place of Revelation | Medina |

| About | Proving the divinity of the Qur'an by negating discrepancy within its teachings |

| Related Verses | Verse 28 of Sura al-Zumar, Verse 1 of Sura al-Kahf, Verse 81 of Sura al-Nisa |

Qur'an 4:82 invites the audience to ponder and reflect upon the Qur'an, stating that if the Qur'an were from anyone other than God, discrepancy would be found within it. Therefore, the negation of discrepancy in the Qur'an proves the authenticity and divinity of the Qur'an. Some scholars have considered the absence of discrepancy as one of the signs of the inimitability (i'jaz) of the Qur'an. Exegetes have divided "difference" (ikhtilaf) into three types: contradiction, disparity, and difference in recitation. Shaykh al-Tusi and 'Allama Tabataba'i have concluded from the command to ponder upon the Qur'an that understanding the Qur'an does not depend on Prophetic hadiths, and ordinary audiences can also understand it.

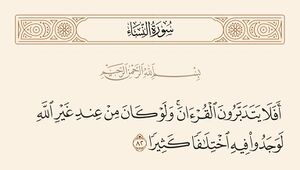

| “ | أَفَلَا يَتَدَبَّرُونَ الْقُرْآنَ ۚ وَلَوْ كَانَ مِنْ عِنْدِ غَيْرِ اللَّهِ لَوَجَدُوا فِيهِ اخْتِلَافًا كَثِيرًا

|

” |

| “ | Do they not contemplate the Qur'an? Had it been from [someone] other than Allah, they would have surely found much discrepancy in it.

|

” |

| — Qur'an 4:82 | ||

Importance of the Verse

Qur'an 4:82 argues for the divinity and truth of the Qur'an by inviting hypocrites and deniers of the Qur'an to reflect upon its verses and their failure to find discrepancy and difference in its teachings.[1]

Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i, a Qur'an exegete, considers this verse an encouragement for the opponents of the Qur'an to reflect upon it, so that it becomes clear that there is no discrepancy in the Qur'an, and this very fact becomes the proof of the Qur'an's divinity for them.[2] Based on this verse, the existence of discrepancy in the contents of a speech is considered a sign of its non-divine nature.[3]

Qur'an 4:82 is one of the important verses cited by proponents of interpretation by opinion (tafsir bi-l-ra'y). They have presented this verse as one of the reasons supporting interpretation by opinion. In the view of this group, human intellect and understanding can access the meanings and contents of the Qur'an by pondering upon it. According to proponents of interpretation by opinion, if the Qur'an has invited us to ponder upon its verses, then it is not logical to simultaneously prohibit Ijtihad and personal opinion (i.e., interpretation by opinion).[4] However, opponents of interpretation by opinion believe that the prohibition of interpretation by opinion does not mean the prohibition of pondering (tadabbur) and thinking about the verses; rather, in interpretation by opinion, the exegete declares his personal opinion before referring to rational and transmitted evidences, without engaging in true reflection upon the verses.[5]

Lack of Discrepancy and I'jaz of the Qur'an

Some exegetes have considered the absence of discrepancy in the verses of the Qur'an as one of the miraculous aspects (i'jaz) of the Qur'an.[6] Al-Shaykh al-Tusi and some other exegetes do not consider the absence of discrepancy in the verses of the Qur'an as one of the aspects of the inimitability of the Qur'an;[7] because discrepancy might not find its way into the speech of some eloquent humans either.[8]

Negation of Discrepancy in the Qur'an

Exegetes have negated the existence of discrepancy in the Qur'an.[9] Nasir Makarim Shirazi, a Qur'an exegete, considers the root of this issue to be the constant change of the mind and psyche of every human being under the changes governing material life.[10] In his view, the passage of time constantly exposes human thought and speech to alteration, and this causes the emergence of discrepancy in their speech; a matter that does not occur regarding God.[11] Exegetes such as Fakhr al-Razi and Muhammad Jawad Balaghi have answered cases mentioned as discrepancies in the Qur'an.[12]

'Allama Tabataba'i, in summarizing the verse, notes that what was revealed to the Prophet (a) at the end of the mission corresponds to what was revealed at the beginning of this period; all branches return to roots and principles, and everything ultimately leads to the Tawhid of the Truth. Any human who ponders upon it judges by his Fitra (nature) that the possessor of this speech is not someone upon whom the passage of days and the transformation and evolution governing the world have an effect, but rather He is the One, Subduing God.[13]

Meaning of Discrepancy

Al-Shaykh al-Tusi says in Tafsir al-tibyan that "difference" (ikhtilaf) means that two things differ in such a way that they cannot replace each other.[14] He divides difference into three types: contradiction, disparity, and difference in recitation. He believes that what is negated in this verse is the difference of contradiction and the difference of disparity, not the difference of recitation. For the difference in recitation, the difference in the length of suras and verses, and the difference in being abrogating or abrogated are not defects or flaws, but are aspects of the beauty of speech.[15] According to Tabataba'i, the absence of discrepancy in the Qur'an means the absence of contradiction (one verse contradicting another), conflict (existence of incompatibility between verses), and disparity (difference between verses in terms of verbal and semantic firmness).[16]

Abundant Discrepancy

Exegetes have considered the qualifier "much" (kathiran) in the verse as an explanatory attribute (qayd tawdihi), meaning that if the Qur'an were not divine, discrepancy would be seen in it, and this discrepancy would be very much.[17] Whereas if the qualifier "much" were a restrictive attribute (qayd ihtirazi), it would only reject the existence of "much discrepancy", but would not negate the possibility of "little discrepancy".[18]

Conclusions from the Verse

Al-Shaykh al-Tusi, the exegete and jurist of the 5th/11th century, believes that four conclusions can be derived from Qur'an 4:82:

- Taqlid (imitation) in Usul al-Din (Principles of Religion) is void and one must investigate them.

- Those who say the Qur'an is not understandable without the hadith of the Prophet (a) are mistaken because the Qur'an has commanded reflection (tadabbur).

- If the Qur'an were from other than God, discrepancy would have penetrated it like human speech.

- Any contradictory speech that is found is not the word of God.[19]

Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i, the author of Al-Mizan, has concluded three points from this verse:

- The Qur'an is perceivable by ordinary understanding.

- Verses of the Qur'an interpret one another.

- The Qur'an does not accept abrogation (in the sense of total invalidation), nullification, completion, or refinement (by others), and no ruler can ever judge against it; therefore, the Shari'a of Islam continues until the Day of Judgment.[20]

Notes

- ↑ Ṭabāṭabāʾī, al-Mīzān, 1394 AH, vol. 5, p. 19.

- ↑ Ṭabāṭabāʾī, al-Mīzān, 1394 AH, vol. 5, p. 19.

- ↑ Hindī, Iẓhār al-ḥaqq, 1413 AH, pp. 307–308.

- ↑ ʿAkk, Uṣūl al-tafsīr wa qawāʿiduh, 1428 AH, p. 169.

- ↑ Riḍāyī Iṣfahānī, Manṭiq-i tafsīr-i Qurʾān, 1387 Sh, vol. 2, p. 290.

- ↑ Zamakhsharī, al-Kashshāf, 1407 AH, vol. 1, p. 540; Rāwandī, al-Kharāʾij wa l-jarāʾiḥ, Muʾassasat al-Imām al-Mahdī, vol. 3, p. 971; Khūʾī, al-Bayān, Muʾassasat Iḥyāʾ Āthār al-Imām al-Khūʾī, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Ṭūsī, al-Tibyān, vol. 3, p. 271; Fakhr al-Rāzī, Nihāyat al-ījāz, 1424 AH, p. 28.

- ↑ Ṭabarsī, Majmaʿ al-bayān, 1415 AH, vol. 3, p. 142; Mullā Ṣadrā, Tafsīr al-Qurʾān al-karīm, 1366 Sh, vol. 2, p. 128.

- ↑ Ṭabāṭabāʾī, al-Mīzān, 1394 AH, vol. 5, p. 19; Zarkashī, al-Burhān, 1376 AH, vol. 2, p. 45; Thaqafī Tihrānī, Rawān-i jāwīd, 1398 AH, vol. 2, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Makārim Shīrāzī, Tafsīr-i nimūna, 1374 Sh, vol. 4, p. 28.

- ↑ Makārim Shīrāzī, Tafsīr-i nimūna, 1374 Sh, vol. 4, p. 28.

- ↑ Fakhr al-Rāzī, Nihāyat al-ījāz, 1424 AH, pp. 242–246; Balāghī, Al-Hudā ilā dīn al-Muṣṭafā, 1405 AH, vol. 2, pp. 5–294.

- ↑ Ṭabāṭabāʾī, al-Mīzān, 1394 AH, vol. 5, p. 20.

- ↑ Ṭūsī, al-Tibyān, vol. 3, p. 271.

- ↑ Ṭūsī, al-Tibyān, vol. 3, p. 271.

- ↑ Ṭabāṭabāʾī, al-Mīzān, 1394 AH, vol. 5, p. 19.

- ↑ Ṭabāṭabāʾī, al-Mīzān, 1394 AH, vol. 5, p. 20.

- ↑ Ṭabāṭabāʾī, al-Mīzān, 1394 AH, vol. 5, p. 20.

- ↑ Ṭūsī, al-Tibyān, vol. 3, p. 270.

- ↑ Ṭabāṭabāʾī, al-Mīzān, 1394 AH, vol. 5, pp. 20–21.

References

- ʿAkk, Khālid ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-. Uṣūl al-tafsīr wa qawāʿiduh. Beirut, Dār al-Nafāʾis, 1428 AH.

- Balāghī, Muḥammad Jawād al-. Al-Hudā ilā dīn al-Muṣṭafā. Beirut, Muʾassasat al-Aʿlamī li-l-Maṭbūʿāt, 1405 AH.

- Fakhr al-Rāzī, Muḥammad b. ʿUmar al-. Nihāyat al-ījāz fī dirāyat al-iʿjāz. Beirut, Dār Ṣādir, 1424 AH.

- Hindī, Raḥmat Allāh b. Khalīl al-Raḥmān al-. Iẓhār al-ḥaqq. Beirut, Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 1413 AH.

- Khūʾī, Sayyid Abū l-Qāsim al-. Al-Bayān fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān. Qom, Muʾassasat Iḥyāʾ Āthār al-Imām al-Khūʾī, n.d.

- Makārim Shīrāzī, Nāṣir. Tafsīr-i nimūna. Tehran, Dār al-Kutub al-Islāmiyya, 1374 Sh.

- Mullā Ṣadrā, Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm. Tafsīr al-Qurʾān al-karīm. Edited by Muḥammad Khājawī. Qom, Intishārāt-i Bīdār, 1366 Sh.

- Rāwandī, Saʿīd b. Hibat Allāh al-. Al-Kharāʾij wa l-jarāʾiḥ. Qom, Muʾassasat al-Imām al-Mahdī, n.d.

- Riḍāyī Iṣfahānī, Muḥammad ʿAlī. Manṭiq-i tafsīr-i Qurʾān. Qom, Nashr-i Jāmiʿat al-Muṣṭafā al-ʿĀlamiyya, 1387 Sh.

- Ṭabarsī, Faḍl b. al-Ḥasan al-. Majmaʿ al-bayān fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān. Beirut, Muʾassasat al-Aʿlamī li-l-Maṭbūʿāt, 1415 AH.

- Ṭabāṭabāʾī, Sayyid Muḥammad Ḥusayn. Al-Mīzān fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān. Beirut, Muʾassasat al-Aʿlamī li-l-Maṭbūʿāt, 1394 AH.

- Thaqafī Tihrānī, Muḥammad. Rawān-i jāwīd dar tafsīr-i Qurʾān-i majīd. Tehran, Nashr-i Burhān, 1398 AH.

- Ṭūsī, Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan al-. Al-Tibyān fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān. Edited by Aḥmad Ḥabīb al-ʿĀmilī. Beirut, Dār Iḥyāʾ al-Turāth al-ʿArabī, n.d.

- Zamakhsharī, Maḥmūd b. ʿUmar al-. Al-Kashshāf ʿan ḥaqāʾiq ghawāmiḍ al-tanzīl. Edited by Muṣṭafā Ḥusayn Aḥmad. Beirut, Dār al-Kitāb al-ʿArabī, 1407 AH.

- Zarkashī, Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-. Al-Burhān fī ʿulūm al-Qurʾān. Edited by Muḥammad Abū l-Faḍl Ibrāhīm. Beirut, Dār al-Maʿrifa, 1376 AH.